Christopher Irvine

A beatitude promises a blessing, but is the blessing for us now, or for after we have died? And if the latter, then we may reasonably ask what of us remains after we have gone? Quite bluntly: what survives after the dissolution of the physical body? There is a multiplicity of possible answers. We could think of what the individual in question has made or achieved—a monument, perhaps, or an enduring foundation and ongoing project that bears the deceased person’s name. There will be the DNA that survives in one’s progeny, and the memories that are held, possibly recorded, by relatives and friends. There are, in other words, physical traces of who we were, such as photographs, things we made, the things we accumulated and valued, as well as a whole array of mental images and memories held by others. But do these do justice to who and what we are as human beings?

The classic Christian view transcends the binary opposition between mind, or consciousness, and matter; it sees the human being as an embodied thinking and feeling subject. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) in his taxonomy of what makes a human being human, spoke of how our sense of being in the world was mediated through the five senses.[1] Characteristically, Aquinas arranged these senses in a hierarchy and accorded the sense of touch as the highest. The sense of touch operates through the sensors just below the skin of the physical body. Even the smallest babies reach out to touch, and through the senses of sight and touch infants begin to differentiate between themselves and others and between themselves and the physical objects of the world around them. So, from an early stage in our human development we gain a sense of the “otherness” of other people and realize that physical objects exist independently of us.

The classic Christian view transcends the binary opposition between mind, or consciousness, and matter; it sees the human being as an embodied thinking and feeling subject.

The Hebrew Psalmist mused over the question of who we are and asked how the Creator God ranks us in the cosmos. This human creature, he says, is just a little lower than the gods, and is crowned, as Robert Alter translates the Hebrew phrase, “with glory and grandeur.”[2] The regal imagery deployed in Psalm 8 speaks of a God-given and therefore inalienable dignity and value. This resonates with the hymn of creation (Genesis 1:27) in which human beings are described as being made in the image of God. The word translated here as image denotes a shifting shadow cast on the ground, suggesting that the outline of this “human form divine,” is the physical human body.

The contemporary artist whose work focuses on the physical human body, and famously uses casts of his own body, is the sculptor Antony Gormley (born 1950). The expressive quality of these body-shaped sculptures, such as those entitled Critical Mass, is shown in the different postures: some bodies are crouching, some kneeling, and others standing. In this ensemble, Gormley goes even beyond Auguste Rodin’s brilliant achievement in showing a moving human figure,[3] and never more so than in his evocative sculpture Rise (1983/4). Here the slight gesture of the raised head suggests an awakening to face a new day. Perhaps the figure is responding, even now, to a promised resurrection, to the stirring of that Spirit who raised Christ from the dead and who gives life to our mortal bodies (Romans 8:11). The play between the physical and the mental, the inside and the outside, the inner life and our external appearance, is further explored in his series of nine prints, Body and Soul (1990)[4].

Today, Gormley’s sculpture certainly resonates with the question of what it is to be a saint, a Spirit-filled person, and it fascinates pilgrims and tourists alike. “Whose body is this?” they wonder.

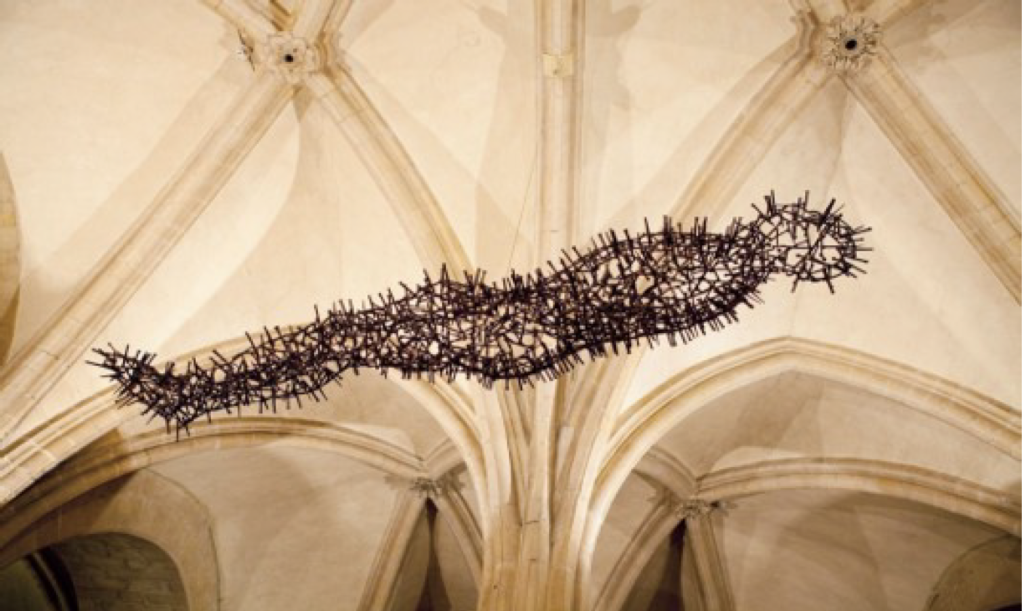

We all know that the material substance of the body is the means whereby a person exists in the physical world. Indeed, we make our presence felt in and through the body. This presence is more than a question of location, of where we are. It also determines to a significant extent who and how we are as we occupy specific spaces here and there. The work that shows this in a startling way is his sculpture Transport (2010), now exhibited in the Eastern Crypt of Canterbury Cathedral. This body-shaped piece, 210cm x 63cm x 43cm, was fabricated from 210 medieval nails saved from the repair of the roof of south transept of the cathedral. The sculpture is suspended by a single translucent cord and floats over the site of the first tomb-shrine of Thomas Becket who was murdered in the Cathedral on December 29, 1170.

Antony Gormley, Transport (2011). Canterbury Cathedral: photograph by Stephen White, London.

In many ways Thomas was an unlikely character to have become a saint, but traces of a Spirit-filled life and death soon attracted increasing numbers of devotees to Canterbury. Today, Gormley’s sculpture certainly resonates with the question of what it is to be a saint, a Spirit-filled person, and it fascinates pilgrims and tourists alike. “Whose body is this?” they wonder. Good art has the capacity to raise important questions such as who we are, and Transport certainly does that. For me the definite bodily outline of the sculpture reminds us that the body is not something we have; it is something that we are. “I am a body,” Nietzsche declared, and Paul tells us that it is through the body that we express our service to God and neighbor (1 Corinthians 6:20 and Romans 12:1).

For those “called to be saints,” living between the time of Christ’s bodily incarnation and the hoped-for resurrection of the body, the body is the site in which the Christian is called to live out the Beatitudes.

As light and air move gently through this floating sculpture we may be reminded that the embodied person in-breathes the very breath of God, giving us the power of movement, thought, and feeling. Put simply, then, the body is the site of consciousness and is not merely a physical shell that we temporarily inhabit. Moreover, for those “called to be saints,” living between the time of Christ’s bodily incarnation and the hoped-for resurrection of the body, the body is the site in which the Christian is called to live out the Beatitudes (Matthew 5:3–11).[5]

As well as recalling us to the essential bodily dimension of our life, the sculptor evokes the more nuanced question of presence. This is powerfully the case in Gormley’s Another Place (1997), a series of cast-iron figures, now placed at intervals along the shoreline on Crosby Beach in Merseyside, England, and which appear and disappear with the rise and fall of the tide. Each of these solid iron sculptures, exposed to the elements, looks out to sea and faces the horizon, the dawning of a new world.

Antony Gormley, Another Place (1997).

If we reflect on Gormley’s body-forms, we may find ourselves asking what it means to be present, that is, present to ourselves as embodied spatial beings in time, as well as being truly present to another. The work of the Swiss painter and sculptor Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966) provides another poignant statement about presence. In the 1950s Giacometti became well-known for his elongated figures. Each of these attenuated bodies has a distinctive and prominent face, and it is the face that is freighted with meaning here.[6]

Perhaps what the Christian sees in the present is the glance of the Other, the gracious and transforming countenance of God, in the face of Jesus Christ, in and through the Spirit.

Following the work of the Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, much has been written about how the face is the index of our living honestly and responsible with ourselves, with others, and before God.[7] For Levinas the face was always the face of the other, and this understanding is certainly rooted in the Hebrew poetry of the Psalms. Here, the word variously translated “face” or “countenance” literally means presence. In Psalm 27, for instance, the reader is drawn into a dialogue between the worshiper and God. The speaker is invited to seek God’s face and responds by saying “your face Lord, do I seek.” The reciprocal gaze that is implied here brings us close to a description of a saint as one whose face, in looking toward the Lord, is radiant[8] and is charged with a greater weight of being. It was the Orthodox theologian Bishop Kallistos Ware who once said that if you wanted to know what a saint looked like you simply had to look at their face.[9]

This brings us back full circle to the Beatitudes, and invites us to reflect more deeply on the sixth beatitude. Blessed, indeed, are the pure in heart, who seek after God, because they will see God. Some may say that this blessing is a future, eschatological reality. It is certainly that. But since the Resurrection of Christ, eschatological realities are reflexive and impinge on the present, on who and what and where we are now. As St. Paul says, now we may see in a glass darkly, but then we will see face to face (1 Corinthians 13:12). Perhaps what the Christian sees in the present is the glance of the Other, the gracious and transforming countenance of God, in the face of Jesus Christ, in and through the Spirit.

In Dante’s Divine Comedy, written around 1307/8, it is the glance of the beloved Beatrice that enables the poet to ascend heavenward. The poet is then drawn to the summit by the radiant light of God’s countenance. As he ascends, he encounters the company of the blessed ones, the saints in glory, appearing as a cloud of faces (Canto 30.41, 31.49). It is the picturing of this vision that may recall for us that other, final beatitude: “Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord” (Revelation 14:13).

Christopher Irvine was formerly Canon Librarian and Director of Education at Canterbury Cathedral. He is a member of the Society of the Resurrection and currently cares for two rural parishes in East Sussex (UK). He is a Teaching Fellow of St. Augustine’s College of Theology, and he also teaches for Sarum College and the Mirfield Liturgical Institute (College of the Resurrection). He has recently contributed an essay on monastic architecture in Oneness, the Dynamics of Monasticism, and is the author of The Art of God, and more recently, The Cross and Creation in Christian Liturgy and Art (2013).

Christopher Irvine was formerly Canon Librarian and Director of Education at Canterbury Cathedral. He is a member of the Society of the Resurrection and currently cares for two rural parishes in East Sussex (UK). He is a Teaching Fellow of St. Augustine’s College of Theology, and he also teaches for Sarum College and the Mirfield Liturgical Institute (College of the Resurrection). He has recently contributed an essay on monastic architecture in Oneness, the Dynamics of Monasticism, and is the author of The Art of God, and more recently, The Cross and Creation in Christian Liturgy and Art (2013).

[1] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologia 1.78.3.

[2] Robert Alter, The Book of Psalms (W.W. Norton & Company: New York, 2007), 23.

[3] See Rodin’s sculpture The Walking Man (c. 1900).

[4] See Antony Gormley (Phaidon: New York, 2000), 128.

[5] The Beatitudes are set in the Lectionary as the Gospel passage for the celebration of the Eucharist on the Feast of All Saints.

[6] See, for example, https://www.fondation-maeght.com/en/collection/selected-pieces/7/alberto-giacometti (accessed 11/8/18).

[7] See, for example, David F. Ford, Self and Salvation: Being Transformed, (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1999).

[8] See Psalm 34:5.

[9] We may also reflect on the icon convention of depicting the full face of the saint. See Constantine Cavarnos, Guide to Byzantine Iconography, vol. 1 (Institute for Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies: Boston, 1993), 28.