Lee M. Jefferson

Now look at Jesus the heavenly physician. Come inside his room of healing, the church.

— Origen of Alexandria (Homily on Leviticus)

In the Book of Common Prayer, the Roman Missal, and in almost any Christian prayer book, there are prayers for healing. Health is a human concern and has always been a focus of prayer among Christians, who pray for the sick whenever they gather for worship.

It certainly is no surprise that health and well-being was also a primary concern in the time of Jesus. Health care existed, of course, but was arguably as difficult to negotiate then as it is now. Physicians could be consulted, but it cost money and was expensive. People could also consult magicians to procure spells to ward off maladies. Quite often the ill and infirm treated their health as a religious matter and turned to gods and goddesses in the Greco-Roman pantheon such as Hercules, Asclepius, and Isis for healing. There were also divine men such as the Greek philosopher Apollonius of Tyana (15–100 CE) who developed a following as a healer. To understand how Jesus is characterized in early-Christian texts and art as a healer and worker of miracles, we must see him within the context of competition among various sources of healing available at the time.

Figure 1: Fresco wall painting, Jesus healing the woman with the blood issue, Catacomb of Peter and Marcellinus, Rome, fourth century CE (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

In the Gospel of Mark, the first canonical gospel, written around 68–70 CE, Jesus is introduced as a healer with the word “physician” (iatros) (Mark 2:17). In the healing episodes in Mark, Jesus is frequently contrasted with other physicians, being like them in terms of healing, but different in the impact his healing has on the patient. In one notable story, a woman comes to Jesus seeking a cure for her hemorrhages. The author of Mark writes, “She had endured much under many physicians, and had spent all that she had; and she was no better, but rather grew worse,” possibly commenting on the efficacy of worldly medicine (Mark 5:26, NRSV). In this pericope the woman is described as going up to Jesus and touching his cloak. Jesus notices that “power left him” as the woman was cured. Jesus thus turns the episode into a discourse on faith, telling the woman that her faith has made her well, and to go and “be healed of your disease.” The healing episode as described in Mark was depicted in early Christian art, a fine example being the painting preserved in the catacomb of Peter and Marcellinus in Rome (Figure 1).

The depictions of the healings and miracles of Jesus as they survive in art before the fifth century demonstrate the continuing need to show the healing power of Jesus over and against other rivals, and the importance of these stories for early Christians. Readers may be surprised to learn that in the early development of Christian art, images of the crucifixion were not of interest to audiences. Instead, images of Jesus as healer and miracle worker were the most prolific.[1]

Why was showing Jesus as healer and miracle worker so important for early Christians? One obvious point is clear: An image of a god (or demigod) that heals the sick and performs miracles is more likely to draw believers than images of a crucified person. Early Christians were interested in promoting Jesus as more powerful than his rivals, and they wanted to exhibit the curative qualities of their religion. At the same time, these images also reveal the laity’s growing need to believe in the miraculous, providing some respite in harsh times. “Healing” and “miracle” may seem to be two different terms, yet in early Christianity they are related. Images of Jesus curing the sick and afflicted or raising the dead gave hope to their audiences and they established Jesus as not only a healer but the preeminent healer.

Much of the earliest Christian art that survives is funerary in nature, being preserved in places where the dead were buried and their lives celebrated. Funerary art in early Christianity was not for the dead but for the living.

Fresco wall painting, raising of Lazarus, Catacomb of Priscilla, Rome, early to mid-third century CE (photo from Joseph Wilpert, Roma sotterranae: le pitture delle catacomb romane, Rome: Desclée, Lefebvre, 1903, pl. 45)

Catacombs in Rome—located outside the city walls, because in Roman practice the dead must be buried outside the city—contain funerary niches and occasionally sarcophagi where the inhumed were laid to rest. Family members and other Christians would come to the catacombs to pray and honor the dead. Both Prudentius and Jerome claim that Christians celebrated the Eucharist in the Roman catacombs, with Jerome recalling how fearful he was of the dark. Jerome records when he was a boy in Rome that he used to visit the crypts of the martyrs on Sundays, and that the bodies of the entombed were on either side encased in darkness, commenting it reminded him of the prophecy, “They descend to the infernal regions alive.”[2] The art in this underground context was important in making tangible, for the living, the power of Christ’s victory over death. Images of Jesus raising the dead to life are featured in many rooms and on sarcophagi (Figure 2). The art gave expression to ideas and represented events described in the scriptures, but their visual impact in a funerary environment also served to inspire Christians to be united in the face of adversity in the polytheistic world that included competing healers and healing gods. Such images were community-building and bound the group in a relationship with their God.

Jesus and Asclepius

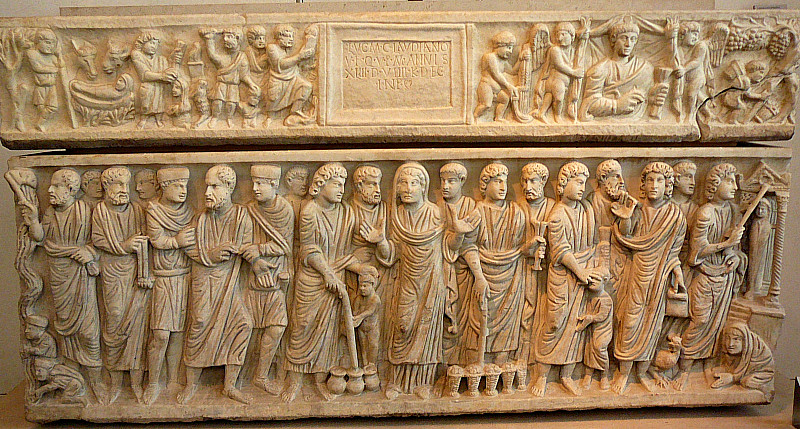

One room in the collection of the National Roman Museum in the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme contains two examples of early Christian funerary sculpture that wonderfully exhibit the importance for early Christian communities of portraying Jesus as a healer and miracle worker. The first example, the sarcophagus of Marcus Claudianus, dates from the fourth century and features several iterations of the various healings and miracles of Jesus that are mentioned in the New Testament (Figure 3).

Figure 4: Marble funerary plaque, Terme fragment, Rome, 290-310 CE, Museo Nazionale Romano – Palazzo Massimo delle Terme (photo: author)

The front of the sarcophagus features a prominent central figure: the orant, a female figure, based on a Roman prototype, that stands with her hands raised in the position of prayer. On either side of this praying figure are episodes of Jesus performing nature miracles, turning water into wine at Cana, and dividing loaves. Jesus is presented as a Roman in typical Roman dress, in toga and pallium, and clean-shaven (many early images of Jesus did not include the iconic beard, a feature that may surprise modern viewers).[3] The narrative of healings and miracles is bookended by Peter striking water from the rock on the left side, and Jesus depicted raising Lazarus from the dead on the right side, touching his burial house with a curious tool or implement that will be discussed below.

Displayed above the Marcus Claudianus sarcophagus in the Terme museum is a funerary plaque, on which representations of Jesus are preserved: he is shown bearded and wearing a toga, his chest bare, as he teaches and also heals with the power of touch (Figure 4). The guise in which Jesus is represented has caused some confusion among scholars regarding the context in which this relief was viewed originally. Some scholars interpret the clothing of Jesus as indicating that he was understood as a Cynic philosopher, given that Cynics were itinerant and were arrayed in the same manner.[4] Others have used this fragment to suggest that in some representations Jesus’s appearance deliberately recalls rival gods, specifically the healing god Asclepius, who was portrayed in a similar manner, as we shall see below.[5]

These two examples of sculpture produced in Rome during the fourth century exemplify the importance for early Christians at this time and place of the idea of Jesus as a dominant healer and miracle worker. In both similar and different ways, the objects demonstrate the environment of the early Christians, one in which monotheists and polytheists lived side-by-side in the Empire. One of the biggest threats to the rise of Christianity was competing religions, including the cult of Asclepius, the Greek healing god, that had been adopted by the Romans. Originally from Epidauros, he was “imported” to different cities to battle outbreaks of disease. Ovid writes of Asclepius’s advent in Rome, that his symbol, the snake, slithered off the boat and onto Tiber Island where his temple stood.[6] Now, the temple has given way to a Christian church, but the serpent imagery on the stone foundation remains.

Asclepius was the son of Apollo, trained in the healing arts by a centaur, and he was killed by Zeus for transgressing his authority. But he was raised to Olympus upon his death. His cultic observance lasted into late antiquity with temples known as Asclepeion serving as de facto healing centers. Patristic authors noted the threat of Asclepius, calling him out by name. Justin Martyr, writing in Rome in the mid-second century CE, mentions him in comparison to Christ, saying “And when we say that he (Christ) healed the lame, the paralytic, and those born blind, and raised the dead, we appear to say things similar to those said to have been done by Asclepius.”[7] Athanasius of Alexandria, writing in the fourth century CE, mentions that Asclepius was deified as a healer but is not comparable to Jesus, who heals not with matter such as herbs but healed mankind with his Resurrection.[8] But Asclepius had his defenders, who ardently believed in the efficacy of the healing cult. Aelius Aristides claims that he lived “many varied lives” due to the power of the god.[9]

Figure 5: Marble, Statue of Asclepius, Rome, Second century CE, Galleria Borghese (photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Asclepius was depicted in a consistent manner, often with a beard (though occasionally clean-shaven), in a toga with his chest bare, and carrying a serpent-entwined staff (Figure 5). The appearance of Asclepius has drawn comparisons to the image of Jesus on the Terme fragment mentioned above (Figure 4). Art could be used to present Christ as analogous to Asclepius or like other gods in appearance, making the Jesus movement more palatable to polytheists. If Jesus were portrayed as similar to Asclepius in appearance, and healing through the power of touch, he could be recognized as a healer akin to Asclepius, only greater.

The testimonies of the cult show that the healing of Asclepius came about through the power of dreams. Asclepius would purportedly visit the patient napping in the Asclepeion and provide a healing remedy or prescription. One blind man testified that the god revealed in a dream that “he should go and take the blood of a white cock along with honey and compound an eye salve,” whereupon he was healed thanks to Asclepius.[10] Unlike the testimonies of Asclepius’s healing through dreams, however, Christian art shows Jesus healing his patients directly, with the power of physical touch as on the Terme fragment above, where a bearded Jesus touches the sick. This feature sets Jesus apart as a healer in the manifest world, not the ethereal realm of the subconscious.

There are several instances in the gospels of Jesus raising the dead, and these are among the most popular scenes for representation in catacomb art and on sarcophagi. The most frequently occuring example is the raising of Lazarus, an event recorded only in the Gospel of John.[11] In this miracle, Jesus beckons Lazarus out of his tomb and also takes special notice of Lazarus’s sister Martha, who acknowledges the messianic status of Jesus (John 11:27). Lazarus is typically depicted in early Christian art as a mummified figure in a little burial house as Jesus touches the dwelling. The raising of Lazarus was a popular scene in a funerary environment as it emphasized the final resurrection and provided comfort for the family of the dead.

The act of raising the dead was also a well-known feature of the Asclepius myth. In fact, several ancient writers attest that Asclepius was slain by Zeus for being too good at his job as a healer: by raising the dead, he made Hades angry. As Pliny the Elder states, “Asclepius was struck by lightning for bringing Tyndareus back to life.”[12] Asclepius transgressed the bounds of his authority.

By exhibiting Christ as a successful raiser of the dead, requiring no permission or authority from above to perform such a feat, Christian art emphasized Jesus as more powerful than other contemporary deities or men acclaimed as healers. Early Christian art was multivalent both in intention and in its reception. An image of Jesus raising Lazarus can provide comfort for the family of the inhumed, remind them of the resurrection secured by Christ for the faithful, and show Jesus as unrivaled, all in one simple snapshot. Another feature of these scenes is the curious inclusion of Jesus using a tool in his healings and miracles. On first glance, it appears that in many of these images Jesus is using some type of magic wand.

The Magic Wand of Jesus?

In catacomb painting and funerary sculpture examples of Jesus healing and performing miracles, he often holds a stylized implement. This could be thin and reed-like, as in the catacomb examples, or thicker and ruddy as in the sarcophagi examples (Figure 6).

There is no mention in any of the gospels of Jesus utilizing a tool in the performance of his miracles. The closest mention is Jesus using saliva or mud in the healing of a blind man in the Gospel according to Mark (Mark 8:22). Yet in these images Jesus appears to be holding what could be called a virga or rabdos, a type of wand in antiquity akin to the caduceus of Hermes. Some scholars have used these images to conclude that late ancient audiences thought Jesus was some type of magician wielding a magic wand.[13] When I show these images to young audiences, their initial exclamation is that Jesus is like Harry Potter, part of the wizarding world of Hogwarts.

However, there are several reasons to think this is not meant to be a type of wand. First, magic in antiquity did not prescribe the use of implements in spells. The efficacy of magic was achieved by the proper recitation and recreation of the spells themselves, not by any type of wand. Second, there are no recovered images of any magician in the performance of their job. This lack of images suggests that wands were not primary in late ancient magic. Furthermore, the early church writers certainly did not want to associate the practice of magic with Jesus, as they deemed magic repugnant and too aligned with polytheism. In these images, Jesus is not a magician; he is a divine healer and miracle worker, so the “wand” must mean something else.

Interpreting early Christian art often means decoding the language of symbols, and making connections to other cognate iconographic figures and images. Jesus’s “wand” does bear a resemblance to the staff of Asclepius, though it lacks the tell-tale serpent and so this connection seems less likely. But there is another biblical miracle worker featured in catacomb art and on early Christian funerary sculpture who accomplishes his feats with a staff-like tool. That figure is Moses.

Moses was understood by early Christians as one of the most important miracle-working figures prior to Jesus.[14] His feats manifested his authority and his connection to the divine. Moses is depicted striking water from the rock and crossing the Red Sea, using his staff in the performance of these miracles. The tool that Jesus wields is not a wand but a staff. This is meant to connect Jesus to Moses, and also to show that the nascent church is the repository of healings and miracles on earth while Christ is in heaven.

These images accomplish that task by showing the staff Jesus wields as being handed down to another figure. On the sarcophagus of Marcus Claudianus, on the far left side, there is a figure striking water from a rock with the staff. However, this is not Moses but Peter. In a non-canonical text, the apocryphal Acts of Peter, the apostle strikes the walls of his jail cell, releasing water, and then baptizes his jailers.[15] This fairly obscure passage from the Acts of Peter had a powerful impact on the creation of images. Peter can be identified on this sarcophagus as he is being arrested by the jailers (recognizable by their hats), next to the striking of the rock scene. The staff of Moses, now bequeathed to Peter, shows that Peter carries on, in the church, the miracle-working power once associated with Moses. Such images remind viewers that the church is that physical place where miracles, especially healing miracles, still happen. The staff is an iconographic reference to the enduring power left to the church by Christ.

On the doors of the church of Santa Sabina, on the Aventine Hill in Rome, are some of the oldest wood carvings in early Christian art. Various scenes from scripture are depicted in relief, including one of the earliest images of Jesus crucified. Among the episodes from the New Testament is Jesus’s raising of Lazarus from the dead and his performance of various miracles, all with the staff (Figure 7). However, the interpretation of one particular scene has vexed scholars and viewers alike: Jesus appears to be ascended and in heaven, where he is encircled by a victory wreath, while standing below, the disciples Paul and Peter are shown reaching up to grasp something that is descending to them, and an orant figure stands in between them (Figure 8). It is unclear what exactly it is that the disciples are reaching for. One suggestion is that it is a cross, enclosed in a circle, for there seems to be a carved line extending out of the circle.

Currently, I am working on this image, using photogrammetry technology to support the theory that this carved line is intentional and not due to age or damage. In light of some of the images discussed here, and the importance of Jesus’s role as healer in early Christian Rome, it seems likely to me that Jesus is represented on this panel as handing down the healing and miracle-working staff to Peter and Paul. In this way, the image communicates to the onlooker a narrative in which the church is the location of physical healing and miracles.

What better place to advertise this message than on the actual doors of a church. The legacy of healing and miracle working is long in the Christian Church, echoed in scripture, liturgy, and art, evoking Origen’s words that beckon the suffering into the heavenly physician’s house, “Come inside his room of healing, the church.”

Lee M. Jefferson is the Nelson D. and Mary McDowell Rodes Associate Professor of Religion at Centre College. He has authored Christ the Miracle Worker in Early Christian Art (Fortress Press, 2014), and co-authored and edited The Art of Empire: Christian Art in Its Imperial Context (Fortress Press, 2015), and contributed chapters to recent volumes such as The Routledge Handbook of Early Christian Art (Routledge, 2018). He earned his M.A. and Ph.D. in religion from Vanderbilt University. His current book project focuses on the doors of Santa Sabina, Rome, and a particular panel featuring Peter and Paul.

Lee M. Jefferson is the Nelson D. and Mary McDowell Rodes Associate Professor of Religion at Centre College. He has authored Christ the Miracle Worker in Early Christian Art (Fortress Press, 2014), and co-authored and edited The Art of Empire: Christian Art in Its Imperial Context (Fortress Press, 2015), and contributed chapters to recent volumes such as The Routledge Handbook of Early Christian Art (Routledge, 2018). He earned his M.A. and Ph.D. in religion from Vanderbilt University. His current book project focuses on the doors of Santa Sabina, Rome, and a particular panel featuring Peter and Paul.[1] The work of Felicity Harley-McGowan should be consulted for crucifixion imagery. The most recreated images were of Jesus raising the dead, Jesus healing the paralytic, Jesus healing the blind, and Jesus healing the woman with the blood issue. Other nature-miracle images show Jesus feeding the five thousand and the miracle at Cana. For more data, consult Freidrich Deichmann, Ikonographisches Register für Reportorium der Christlich-Antiken, Band I, Rom und Ostia (Wiesbaden: F. Steiner, 1967); and my Christ the Miracle Worker in Early Christian Art (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2013).

[2] Jerome writes of this in his Commentary on Ezekiel (40. 5-13; PL 25; col. 375). Writing in 380 CE, Jerome’s commentary could be the earliest recovered description of a catacomb in Rome. Prudentius writes more descriptively of the tomb of Hippolytus in his hymn, see Peristephanon 11.153-60 (PL 60; see LCL 398).

[3] For more on the beard of Jesus in art, see Paul Zanker, The Mask of Socrates (Berkeley: UC Press, 1995); and Robin M. Jensen, Face to Face: Portraits of the Divine in Early Christianity (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2005), 154–157.

[4] John Dominic Crossan, Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1994).

[5] Thomas Mathews, The Clash of Gods (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), 72.

[6] Ovid, Metamorphoses, 15.736-41.

[7] Justin Martyr, First Apology, 22.

[8] Athanasius, On the Incarnation, 49.

[9] Aristides, Oratio, 23.15-18. For complete testimonies on Asclepius, see Emma and Ludwig Edelstein, Asclepius: A Collection and Interpretation of the Testimonies (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1945, 1988).

[10] Inscriptiones Graecae 14.966 (second century CE) see Wendy Cotter, Miracles in Greco-Roman Antiquity (New York: Routledge, 1999), 18.

[11] The raising of Lazarus occurs in sixty-five extant examples or Roman sarcophagi, far outpacing images of Jesus raising Jairus’s daughter, the widow’s son at Nain, or Jesus as Ezekiel in the Valley of the Dry Bones. See Deichmann, Bovini and Brandenburg, Reportorium der Christlich-Antiken Sarkophage, Band 1, pts. 1, 123.

[12] Pliny, Natural History, 29.1.3.

[13] Mathews concludes as much, see Clash of Gods, 54–89. Also see P.C. Finney’s rebuttal in “Do You Think God is a Magician” in Akten des Symposiums Früchristliche Sarkophage (Deutches Archäologisches Institut, 1999), 99–108.

[14] Origen calls Moses one of two men who have been given to the human race who performed miracles, the other being Jesus (Contra Celsum, 1.45).

[15] Acts of Peter 5 (Linus text). See David Eastman’s The Ancient Martyrdom Accounts of Peter and Paul (Atlanta: SBL Press, 2015).

—

This material is licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Recommended Citation: Jefferson, Lee M. (2019): “The Heavenly Physician: Jesus as Healer in Early Christian Art,” The Yale ISM Review: Vol. 5: No. 1, Article 5. Available at https://ismreview.yale.edu