Cathy George

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

How might the beatitude, “blessed are the poor in spirit,” from Matthew’s Gospel, offer us insight into the faith of a child?

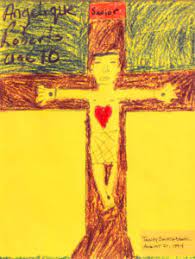

Angelique Roberts was ten years old when she drew the picture of Jesus that hangs on the wall above my desk. Blue crayon colors the sky behind the brown wooden planks that form a cross. There is an orange rectangular sign above his head with the single word—“Savior”—written in deep purple. Circles of lead fill in the nails on the hands and feet of the nearly naked young man drawn in pencil. A stylish short haircut, shaved above the ears, tightly curled and cropped on top, frames his broad facial features, giving him a handsome, distinctive look. Beneath groomed eyebrows, a large oval tear rolls onto his cheek beneath the dark slit of one eye. A bright red heart covers his torso.

Angelique Roberts was ten years old when she drew the picture of Jesus that hangs on the wall above my desk. Blue crayon colors the sky behind the brown wooden planks that form a cross. There is an orange rectangular sign above his head with the single word—“Savior”—written in deep purple. Circles of lead fill in the nails on the hands and feet of the nearly naked young man drawn in pencil. A stylish short haircut, shaved above the ears, tightly curled and cropped on top, frames his broad facial features, giving him a handsome, distinctive look. Beneath groomed eyebrows, a large oval tear rolls onto his cheek beneath the dark slit of one eye. A bright red heart covers his torso.

Angelique walked over to me, extending her hand with her drawing in it and said, “This is for you. It’s a picture of Jesus.” Most Sundays, as she and her classmates formed a line to return to church from the children’s homily, she raised her hand high as she could stretch it, flapping her fingers back and forth, hoping to be chosen to carry the basket that collected their prayers and pictures down the center aisle to place it on the altar. As I looked at the picture that she handed to me, she said, “It’s Jesus, and it’s my brother who died. He was so nice, Reverend Cathy. He was my best friend. He didn’t do bad stuff or hang with gangs, and he didn’t have any guns. He always looked out for me. He was walking home from school when someone drove by in a car and shot him.”

In 2016, firearm injuries were the third leading cause of death for children between the ages of one and seventeen in the United States. An average of four children per day died from a gun injury.[1] Eighteen percent of children in the United States—over 13 million—were living in poverty.[2] More than 92,000 children were removed from their home because a parent had a drug-abuse issue,[3] and over 437,000 were in foster care.[4] The circumstances that gave rise to these grim statistics have not changed substantially since that time.

Jesus’s innocent death on the cross was a balm for Angelique as he hung with and for her brother. She turned to the cross of Christ in her unfathomable loss, where her Savior was united with her brother in his death.

Children are at home in the spiritual realm; it is their nature to believe in what they cannot see.

Matthew’s gospel tells us that Jesus’s disciples jockeyed for position and attempted to impose a hierarchy of greatness on the community of his followers. When they came to him with the question, “Who is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven?” (Matthew 18:1–5), Jesus answered them by calling a child at play to come from the sidelines. He placed the child in the midst of them. Jesus didn’t elevate the child onto a stage, or seat one at his right and another at his left; there were no thrones, no crowns, no spiritual medals, no better or best. He placed a child among them and said: “Whoever welcomes one such child in my name, welcomes me.” Children have no standing, no position, no authority, no money. They are dependent upon others for their food, clothes, and safety—for their very survival. Jesus parted the crowd of adults to make room for children in order to demonstrate what greatness is. “Truly I tell you,” Jesus said, “unless you become like children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 18:4).

Children are at home in the spiritual realm; it is their nature to believe in what they cannot see. Their vivid, often wild imaginations are not distanced from their innate spirituality by knowledge and reason. Innate spirituality is a perceptual and intellectual faculty that allows us to feel part of something larger than ourselves. It lets us experience an interactive relationship with a guiding, ultimately loving presence that is with us from birth. Spirituality both precedes and transcends language, culture, and religion. It is as natural to a child as is their fascination with a butterfly or a boat. According to Lisa Miller in her research on the spirituality of children, The Spiritual Child; The New Science on Parenting for Health and Lifelong Thriving, “The confluence of evidence is clear . . . biologically, we are hardwired for a spiritual connection. Spiritual development is a biological and psychological imperative from birth . . . the innate spiritual attunement of young children—unlike other lines of development—appears to begin whole and fully expressed.”[5]

As we mature in faith, our knowledge of God and of our tradition increases, but often at the expense of the imaginative, connected spiritual life that we had the capacity for as children. Our prayer life is often divorced from our daily life and surroundings. Adults lose the honesty and humor that children bring to prayer. It frequently becomes an extraneous exercise, often a duty. Children, on the other hand, are blessed in prayer by their fearless neediness. Children pray what they feel, not what they think. Their spontaneous manner becomes a blessing in the spiritual realm, in the kingdom of heaven. This is what leads Jesus to place them in the midst of adults and draw attention to their patterns of life.

The silence taught us to listen to ourselves, to hear what we wanted to bring to God in prayer.

At Sunday liturgy, when I was not in the pulpit, children joined me in the center aisle, and we walked out of the sanctuary during the singing of the sermon hymn. In an adjacent room with many windows and abundant light, we sat on a huge carpet spread on the shiny pine floor. We sat together in silence for one minute (using a kitchen timer and waiting for the ding before speaking). The silence taught us to listen to ourselves, to hear what we wanted to bring to God in prayer. Older children passed out colored markers and small pieces of paper. Children who could write wrote their prayers and embellished them with drawings. The only noise in a group of twenty or so children, was someone asking for a particular color of marker to be passed, or the sound of crumpling paper as a child reached for a fresh page to begin again.

Whenever I am discouraged—when my work strays far from the passion for God that drew me into spiritual leadership—I reach into the large shiny bag filled with the prayers of children, prayers that I saved from Sunday to Sunday. The children’s honesty and humor bring me back. They help me to pray.

Dear God, I kicked the ball in the wrong goal and all my friends are mad at me. Can you help me?

Dear God, My best friend’s Mom had to go to a hospital kind of place for awhile, please take care of my friend while her Mom gets better.

Dear God, My Grampa is sort of mean, will you please make him nicer?

Dear God, My teacher’s cat is sick, please make it better.

Dear God, Dad was sad last night, and I am worried about him. Please make him happy again.

Dear God, My Grama’s dog got lost, please find her, she is Grama’s best friend.

Dear God, Please let me remember everything when it is time to take the test.

Often their prayers are simple questions:

Dear God, In Sunday School they told us what you do. Who does it when you are on vacation?

Dear God, I read the bible. What does begat mean? Nobody will tell me.

Dear God, Are you really invisible or is that just a trick?

Dear God, Do animals use you or is there someone else for them?

Dear God, Thank you for the baby brother but what I prayed for was a puppy.

Dear God, Please put a holiday between Christmas and Easter, there is nothing good in there now.

Dear God, Please send me a pony, I never asked for anything else. You can look it up.

Dear God, Please send Dennis Clark to a different camp this year.

Dear God, If you watch in church on Sunday I will show you my new shoes.

Dear God, I love you because you give us what we need to live, but I wish you would tell me why you made it so we have to die.[6]

Children pray their life.

How many times have we kept ourselves from praying for what we really want because we have an idea that . . . what? That God doesn’t care if we find the love we long for or the job we dream of? When kids want their team to win, or to pass a test, or find a new friend, they do not hesitate to ask God for these things. If they are worried about how hard their mom works or see their dad crying, they pray for them.

Who wants to keep praying when we are not praying about what we truly care about? Who wants a prayer life that judges our prayers as unworthy, or wrong? Who wants to pray when you think you will never get it right, never do it enough, and never be good at it? These barriers don’t block the blessed hearts of children at prayer. Children pray their life.

I wonder if Jesus called them close to him because their humor and humility brought him back to himself—perhaps in the same way that going off to the mountains, or getting in a boat and rowing out on the water did.

Try seeking out children when you have lost your way at prayer. Part your way through a group of adults and talk with a child. Ask them what they think God is like and whether they ever talk to God. Lacking the delusion of self-importance, children are blessed in their connection to God, because of what they do not yet possess. That poverty of spirit blesses their prayer lives, and it blesses ours.

Rev. Cathy H. George is Associate Dean and Director of Formation for Berkeley Divinity School at Yale.

Rev. Cathy H. George is Associate Dean and Director of Formation for Berkeley Divinity School at Yale.

[1]. Christopher Ingraham, “More than 26,000 Children and Teens Have Been Killed in Gun Violence since 1999,” The Washington Post Wonkblog, March 23, 2018.

[2]. “Child Poverty in America 2016: National Analysis,” Children’s Defense Fund, last modified September 18, 2017. http://www.childrensdefense.org/library/data/child-poverty-in-america-2016.pdf.

[3]. “Number of Children in Foster Care Continues to Increase,” Administration for Children and Families of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, last modified November 30, 2017. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/media/press/2017/number-of-children-in-foster-care-continues-to-increase.

[4]. Ibid.

[5]. Lisa Miller, The Spiritual Child: The New Science on Parenting for Health and Lifelong Thriving (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2015), 29.

[6]. Stuart Hample and Eric Marshall, Children’s Letters to God (New York: Workman Publications, 1991).